Adventures

in Surround Sound, from 7.2 to Quad Adventures

in Surround Sound, from 7.2 to Quad

(personal

and historical notes, basics, and acoustic realities often

forgotten)

= P

a r t 1 =

|

Introduction Introduction

5.2

Channel Surround Mixing Studio

(click

image for a huge view!)

Finally

it seems to be happening! In 2001 we don't yet have Hal

(check back

in another 100 years ;^),

but we do have a distinct buzz-on about Surround Sound --

for film soundtracks, DVD's, and for music creation and

mixing, as the new DVD-A standard is designed to implement.

To me it seems like it's taken forever. I'd nearly given up

hope that a practical surround sound system would reach the

public in my lifetime, anyway. Those of us who lived through

the big Quad Boom and Bust of the 70's are gun shy,

expecting another stillborn standard, based more on hype

than reality, and something valuable gained for effort

expended. Just a few weeks ago I checked in again on what's

become available online in web pages around the globe. Well,

welly, there's a good representative amount of information

starting to appear already -- on Quad, 5.1

(five

full-range channels and one sub woofer with one tenth the

range, or ".1", total = 5.1),

and several other options. Yeay, this is a healthy sign!

Could it be?! Finally

it seems to be happening! In 2001 we don't yet have Hal

(check back

in another 100 years ;^),

but we do have a distinct buzz-on about Surround Sound --

for film soundtracks, DVD's, and for music creation and

mixing, as the new DVD-A standard is designed to implement.

To me it seems like it's taken forever. I'd nearly given up

hope that a practical surround sound system would reach the

public in my lifetime, anyway. Those of us who lived through

the big Quad Boom and Bust of the 70's are gun shy,

expecting another stillborn standard, based more on hype

than reality, and something valuable gained for effort

expended. Just a few weeks ago I checked in again on what's

become available online in web pages around the globe. Well,

welly, there's a good representative amount of information

starting to appear already -- on Quad, 5.1

(five

full-range channels and one sub woofer with one tenth the

range, or ".1", total = 5.1),

and several other options. Yeay, this is a healthy sign!

Could it be?!

(Note:

This next section contains an historical note on my own

first encounters with surround sound. Click

HERE

to skip forward to some of the basics on surround audio,

which we'll be discussing on these pages.)

Okay, I have reason to be

more skeptical than most of you reading this. My first

experimentation with surround sound took place way back when

I was still in college, studying music composition and

physics. For me, surround sound predates the Moog

Synthesizer. At that time there was no technology one could

readily purchase to do more than the same old two-channel

Stereophonic Sound that seems to be going on, like forever.

Of course just TWO tracks was big news those days. So I had

to build my own first "quad" tape recorder. Four channels,

recorded on four tiny tracks, using two quarter-track tape

heads in what we'd call a "semi-staggered" array. The

hardware was from Viking of Minneapolis, bless them. They

allowed even a very financially challenged student to save

and purchase some very practical tools with which to record

and playback music and sounds. I had to find a way to

synchronize the four bias oscillators, and also constructed

(from scratch) a sturdy wooden enclosure to mount it all in.

It had a handle on it (since broken off), so it was

"portable." At 45 pounds, I leave it to you to decide how

realistic this description was.

Custom

Viking Four-Channel Tape Recorder

Above

you can see it with the cover removed. I was astonished how

good it still looked when I discovered it in my parent's

basement some dozen years ago. I've cleaned, reworked and

adjusted it, gotten it to work well again, another surprise.

This is the machine that I made my first multichannel

recordings on. I took it with me to several concerts given

in Providence and at Brown University, and made quite a few

"amateur" surround recordings, experimenting with microphone

and speaker placement, since there were few to no books on

the subject. I learned a lot about what works and what

doesn't by uninhibitedly trying every crazy idea out for

myself. My early electronic acoustic music compositions were

created with the custom Viking, and when I came to New York

City to Columbia for Graduate Work in composition it came

along with me, need it or no!

But

by then I had begun to use Ampex professional tape machines.

Peter M. Downes, a good older friend who made custom

recordings in the Providence area, generously let me borrow

his 2-tk Ampex 351 and Magnecorder for one entire summer, to

create the sounds for Episodes for Piano and Electronic

Sound. My four-track Viking was used on that work, too. But

the prestigious Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center

had many professional Ampex machines, including three (!)

that made me drool: 1/2" four-track 300-4's -- cool! "How

ya' gonna keep 'em down on the farm," I learned quickly how

to use these sturdier, better sounding tools, and the little

Viking sat unused most of the rest of the time, except to

record a few more live concerts. Later it was moved back to

my parent's house when I relocated, and I forgot about it

for nearly 25 years. Hey, there were new

"toys" to explore!

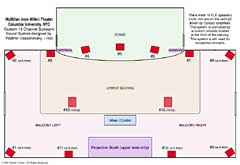

McMillin

(now Miller) Theater's 13-Channel Surround

System

One

of those "toys" was not so much a device as it was an idea:

multi channel surround sound. As the luck of timing would

have it, my favorite professor, composer Vladimir

Ussachevsky, had recently designed and installed a wonderful

new sound system in Columbia University's McMillin

Auditorium (as it was then called). The diagram above is a

plan of the auditorium, showing in red the 13 speaker

channels that had been mounted and wired into a unique

installation. I still drool about the wonders one could

produce at large scale in the new field of multidirectional

audio. There are actually 19 speakers, as the balcony

interfered with producing sound at both levels from once

source apiece. So channels 1, 2, 8, 9, 10 and 11 required

two speakers each, one upstairs, the other down (which are

superimposed in this plan view). The rest are single

speakers per channel. There are also two, #12 and #13, that

were mounted up on the ceiling, facing down! The KLH

loudspeakers for channels 4, 5, and 6 were stored backstage,

and had to be brought out when needed, then positioned as

shown (connectors were nearby).

One

oversight: there should have been two more, above the exit

doors (mid-wall between #1 and 2, and also #8 and 9), at the

exact sides. Live and learn.

It was all fed from a

small room located near the upper speaker 1, which contained

sturdy metal shelving with an appropriately large number of

Dynaco power amps, a Stereo-70 for the double-spkr channels,

Mono-60's for the rest (got pretty hot in there!). Tie-lines

led down to the small electronic music studio, Room 106, in

which I composed most of my electronic music as a student

(it's now used as an office). The studio contained 5 to 8

Ampex tape machines at any one time, the outputs of which

could be fed out to the hall's system. I continued my

experimentation with surround sound, finding out what worked

as planned, and the many more ideas that simply didn't work.

A good "woodshedding experience", I learned a lot, and had a

lot of fun with it, as you might imagine!

|

(Top

of the Page)

(Top

of the Page)

Nomenclature

and Full 7.2 Monitoring Nomenclature

and Full 7.2 Monitoring

Since

the 60's I've been using four or more channels on the

mixdowns of most of my performances and compositions. It's

been a life's desire to get some of this surround music into

the hands of music listeners. And that may very well be

happening soon. I also discover I've accumulated quite a few

"barnacles on the hull" from working in multichannel sound

all these decades. I'd like to scrape some of these off onto

the next generation to figure out what the $%#* to do with

some of them! That was the major motivation for creating

this web location. We'll be referring to speaker

arrangements (very important, that) and the several output

channels a lot on these pages. So let's show the

near-standard labels we'll be using. Here's the same image

at the top, smaller and with labels in red pasted over the

front of each speaker. The two subwoofers are down below

this view, on the studio floor one step below the level of

this shot, and so we've just positioned arrows that show

where they physically are located. There's nothing

surprising going on here, but we wanted to define our terms

clearly. Since

the 60's I've been using four or more channels on the

mixdowns of most of my performances and compositions. It's

been a life's desire to get some of this surround music into

the hands of music listeners. And that may very well be

happening soon. I also discover I've accumulated quite a few

"barnacles on the hull" from working in multichannel sound

all these decades. I'd like to scrape some of these off onto

the next generation to figure out what the $%#* to do with

some of them! That was the major motivation for creating

this web location. We'll be referring to speaker

arrangements (very important, that) and the several output

channels a lot on these pages. So let's show the

near-standard labels we'll be using. Here's the same image

at the top, smaller and with labels in red pasted over the

front of each speaker. The two subwoofers are down below

this view, on the studio floor one step below the level of

this shot, and so we've just positioned arrows that show

where they physically are located. There's nothing

surprising going on here, but we wanted to define our terms

clearly.

Speaker

Locations, 5.2 Channels

Actually,

this view with labels does not fully describe my studio's

monitoring setup. (Please

note: there's a good 12' between the back of the console

showing at the center bottom, and the old 45" video monitor,

the C speaker on top, right in between LF and RF. This

Cinerama-like WA view "squishes" that distance together,

while it also slightly exaggerates the space between LS and

LF, RS and RF.) There

are four more speakers that are not seen in this angle,

driven by another two channels of amplification. These are

located to the rear on both sides of the mixing space, where

they form a blurry impression of diffuse information behind

you and to the sides, surround channel information. I've

been using some modest Pinnacle speakers and a small stereo

amp for this job, as all surround information of this kind

is deliberately narrower, in frequency range and dynamics,

than what the other channels reproduce. For DVD or LaserDisk

playback, the "rear" information from either Dolby Surround

or discrete 5.1 tracks is fed to these channels, as well as

some mixed to LS and RS.

But for music mixing,

these small rear speakers are driven by auxillary channels,

usually ambience and antiphonal parts, or processed

reverberation and echo effects. When used, the extra

channels raise the total channel count to 7.2. That creates

a very impressive soundfield, you bet, and regularly

astonishes visitors here who've never heard that many

channels before! Since 7.2 is really just an extension of

5.1, we'll handle the latter on this web page. Just bear in

mind that it's likely at one time or another that you may

encounter another two or more channels, and that these fully

"behind you" channels are not as important as the other five

plus. You can create a similar directionality by

manipulations of the signals fed to the primary five

surround channels.

There are also cinema

systems in which the additional two channels of 7.1 or 7.2

are used as screen speakers, much as the Stereophonic Sound

for Cinerama and (70 mm) Todd/AO were developed in the 50's.

Here the new channels are added to the front, at the

screen's mid-left ("left-center") and mid-right

("right-center"), forming: L-LC-C-RC-R.

In these cases the surround info is generally the same LS/RS

pair as in 5.1 Surround (or Todd/AO's plain mono surround),

reproduced over side and/or rear "house" speakers. There

have also been films made with a Dolby-matrix encoded

Center-rear channel. That's just a quasi-channel derived

using what we're calling the LS/RS stereo pair, and

represents a pretty modest overall addition,

IF

you've already gotten the rest of the channels

optimized.

When I was working on

the six-channel sound mix for my score to Disney's

TRON,

I had to cheat a little, and used the system as you see it

below while sitting back further than usual to check

balances. That allowed the five main Klipsch speakers to

monitor all five screen channels, while several other rented

speakers served as rear surround channel monitors. Later I

added the four small Pinnacles for that less-critical task.

You can do the same thing if you encounter a need to mix to

five screen channels by moving the side speakers inwards

towards the front, or by relocating your seating position

backwards a few feet to check balances. BTW -- it sounds

wonderful even even if you don't move back, a really

stunning WIDE sound! That will collapse to screen width in a

theater, of course...

In a good theater you

can expect many speakers to be used for the surrounds,

distributed about the auditorium's side and rear walls, even

(bad idea) the ceiling! Dolby recommends many speakers to

create an even "omniphonic" distribution of surround

information, most helpful when there's only a single

channel, as the LCRS of the Dolby Stereo matrix makes

available. With the stereo surrounds of our latest discrete

digital audio you won't need so much non-directional

diffusion. But two additional screen speakers can be

marvelously effective. If done properly with a really

BIG

screen, L-LC-C-RC-R

provides precise images from the screen, more subtlety of

position, and is less affected by where you sit. Given that

screens have shrunk continuously since the mid-60's

(multiscreen multiplex mania) the distinctions are probably

lost. Mixing all dialog and most screen effects in mono to

the center has done even greater disservice to film

stereophony, IMHO.

Speaker

Locations, All 7.2 Channels

Above

you'll see the full 7.2 channels, in an imaginary overhead

view (that

"burnt orange thing" in the center is my actual studio

chair), of an idealized

studio similar to the one shown in the photos above.

Gradually we're going to work backwards, going downwards in

complexity and number of channels, until we reach classic

quadraphonic sound (and a couple of amusing variations), and

the best way to configure THAT 30 year old system. There's

really nothing new in the idea of creating music albums and

film soundtracks on multichannels, certainly not since

Disney's 1940 breakthrough animated feature,

Fantasia.

This film pioneered the idea of surround sound

("Fantasound," no less) and stereophony with a six channel

auditorium presentation using four optical tracks (three of

audio, the fourth was for front/rear steering). Credit

William Garity for most of the engineering, the same

excellent engineer who helped design their legendary

multiplane animation camera. Our tools have become a lot

more sophisticated and easier to use since then. Audio

quality is remarkably better as well, nearing the

theoretical maximums for human hearing and physical

acoustics. It's how we'll use them that will determine their

success in the marketplace, or not, like the quad boom and

bust of the early 70's. It's up to us.

This is the place to

mention, for those interested, what speakers are being shown

above. I became very attached to the Klipschorns when I was

in college. My music professor, Ron Nelson, had a pair of

them, with a central non-corner version in the middle, a

common method of using Paul W. Klipsch's horn-type speakers.

If you put one in each corner in many cases they would be

more than 90 degrees apart. The derived center speaker

helped to fill this gap somewhat. Anyway, Rachel Elkind and

I tried two horn versions in the brownstone studio when we

first move into there. Unfortunately, with the shape of the

room the corner placements were really impractical. That

would have positioned them either behind us, or very far

away in front. The dealer suggested we try the newer

"Cornwall" type (yas

-- that Klipsch model name means you can "use them in a

corner or along a wall" -- no

comment!). We made

careful comparisons for several weeks.

What we learned is that

if you made up a 3 dB loss for the Cornwalls, and then did

not exceed their already hefty maximum excursion, the sound

was nearly exactly alike between the corner horns and these

compromise versions. We were going to have four channels, so

loudness was no worry at all, not with such high-efficiency

speakers that 2 watts would fill a room! Anyway, I got

attached, as I said, to these venerable designs, and aside

from a few upgrades we made later, have used them ever

since, a reliable yardstick I can trust for all my work.

The lowest octave,

though, was always a bit weak with the Cornwalls. That was

the only other tradeoff. For years I tried small equalizers

in the monitor loops to "correct" for this. But at the time

Jim Jensen at Sterling Sound did his usual fine job cutting

my Beauty

in the Beast LP

masters I found a much better answer: "Say, what kind of low

end speakers are those, Jim?" Velodyne Subwoofers? --

Yowsah! These are active feedback, servo-corrected speakers.

I could spend a whole page singing their praises. Simply the

only game in town, far as I'm concerned. The servo feedback

corrects any and all errors. If only this trick worked above

a certain frequency (around 300 Hz), all speakers could be

near-perfect. Alas, it doesn't, as the piston-like action of

the deep bass motion gives way to more complex vibrational

modes, and no one feedback spot can correct for the whole

cone. Oh, well, where it does work, why not go for it?

You'll read below that

I had to decide between one 15" Subwoof, or two 12" units.

This was settled by trying out both carefully with a lot of

my own program material. Then the store allowed me to try it

here, and there was no argument. The servo made both sizes

very very similar in sound. The large size was slightly

louder. But two 12's were ever better, and there was

actually some directionality gained. So you'll see above and

just below the setup the way I have it, with

SWL

and SWR

located midway between the LS-LF,

and RF-RS

pairs. Works great!

This

is also a good time to apologize if I've overlooked

someone's favorite surround sound configuration or idea in

this very incomplete essay. Every opinion herein rests on

several reasonable experiments and follow-ups carried out

over a lifetime. That certainly in no way implies any pose

of "infallibility." But at least what errors or missing

concepts will be found here ought be in the "second and

third orders of subtlety." And I encourage each of you to

try things out, discover like I've discovered, what

actually works for ear, and what is only visual

chauvinism at work again in audio -- where it sure

doesn't belong. That's why I now have to turn a skeptical

eye on many of the sillier ideas being hyped as "fact."

Factoids" is more like it, or Urban Legends (question: are

there any suburban legends? How about rural?). For

myself, I'll stick with what's presented here, at least

until something better comes along, the old scientific

method: zeroing in very slowly on what's

very probably true...

|

(Top

of the Page)

(Top

of the Page)

The

Main 5.2 Channels The

Main 5.2 Channels

Ideal

Surround Speaker Placement -- 5.2

Channels

Fine,

let's for the time being forget about those extra two

channels. Here's the above view of our idealized monitoring

system. The main speakers, LS, LF, RF, and RS, are

equidistant from the listener and positioned at 60 degree

separations. LF and RF are bisected by C, which can be a

slightly smaller speaker from the same family of speakers,

since the bass frequencies are often routed to the bigger

speakers. But that point becomes moot when you have

subwoofers. In this case I made a trade off for two smaller

subwoofers instead of one larger one. With careful A/B

comparisons I learned that the bass was nearly the same when

the two smaller units were working together as a team as

with the single larger unit. But there was, contrary to what

I had read, a small amount of additional directionality

present with the two subwoofs compared to one. Yes, on

steady tones and those with slower attacks you heard little

difference. But on transient waves, hard attacks,

dynamically changing signals, you began to perceive a small

amount of stereo effect with the two, SWL

and SWR,

as shown above. I went with that arrangement, you may prefer

the other choice, while the cost is similar. Fine,

let's for the time being forget about those extra two

channels. Here's the above view of our idealized monitoring

system. The main speakers, LS, LF, RF, and RS, are

equidistant from the listener and positioned at 60 degree

separations. LF and RF are bisected by C, which can be a

slightly smaller speaker from the same family of speakers,

since the bass frequencies are often routed to the bigger

speakers. But that point becomes moot when you have

subwoofers. In this case I made a trade off for two smaller

subwoofers instead of one larger one. With careful A/B

comparisons I learned that the bass was nearly the same when

the two smaller units were working together as a team as

with the single larger unit. But there was, contrary to what

I had read, a small amount of additional directionality

present with the two subwoofs compared to one. Yes, on

steady tones and those with slower attacks you heard little

difference. But on transient waves, hard attacks,

dynamically changing signals, you began to perceive a small

amount of stereo effect with the two, SWL

and SWR,

as shown above. I went with that arrangement, you may prefer

the other choice, while the cost is similar.

Modified

Front Speaker Placement -- 5.2 Channels

I've

seen setups more like the one above. What's different from

the view just above is that the LF

and RF

speakers have been rotated not to be so toe-in as before,

and the center speaker has been brought slightly closer in,

more as many three channel monitors are located in mixing

theaters and even small home theaters. It's not a big

change, and is one we'll pick up again below. If the

listening room is not as deep as it is wide, these mild

repositionings will be appreciated. The sound will not be

greatly affected at all, unless you can compare the two

setups one immediately after the other. Then you may hear a

slight reduction of the in between imaging. But it won't be

any worse than when you listen to two-channel stereo from

slightly off the exact center spot. It's not going to

destroy the surround sound field, but I bring it up as it

has become somewhat common.

Symmetrical

Surround Plan -- 5.2 Channels

On

the other hand, there is also good reason for making the

opposite modification of the front channels, like the

symmetric plan above. The 180 degree surround arc of sound

has been nearly divided into four equal angles, five

discrete channels of sound, plus stereo subwoofers. My

personal experience suggests that instead of going with the

mathematically exact division, yielding all angles of 45

degrees, this version is slightly better perceptually, with

40 and 50 degree angle pairs. It's probably splitting hairs,

but try both and see if you don't agree. We have a slightly

more acute perception of angular displacement of sound

positions when both ears are nearly balanced, facing a

central sound source in front. (It

tends to follow a cosine curve function in front of us, with

a maximum acuity at zero degrees straight ahead, falling off

towards the sides. Behind us our external ears reduce the

absolute value of this function by about 50% or more.)

The above plan

positions the LF

and RF

channels somewhat closer together, nearer to

C,

favoring that most sensitive area. This setup obviously

requires a good, active center channel. Here I've shown the

same smaller C

speaker as before. The subwoofers take care of all the bass

frequencies you could stand, so that's not much of a

compromise. Notice that for monitoring just four channels of

"quadraphonic" material, the missing C channel would leave

an impossible "hole in the middle" between

LF

and RF,

if the above configuration were chosen (40 + 40 = 80 degrees

apart -- yikes!). If you have to check on a lot of 4 channel

material you'd be better off with the first or second layout

above. But for 5.2 channels of music, this one's unbeatable

-- have

yourself a ball!

|

(Top

of the Page)

(Top

of the Page)

Digression

I -- Classic Blunders to Avoid Digression

I -- Classic Blunders to Avoid

The

Worst Quadraphonic Setup -- 4 Channels

Sometimes

the eye can fool the ear into thinking things are fine and

jolly, when they ain't. We can all count the four corners of

a typical room (har-dee-har, my studio is semi- trapezoidal,

and has SIX corners!) or studio. When the first quadraphonic

sound was being introduced in the early 70's guess where

they put the speakers (you've had enough hints)? Yup, just

like the image above, one for one. It also seemed like a

nice, democratically evenhanded approach, we have 360

degrees to split up, let's see now, 4 goes into 360... And

we get this "classic" setup in name only. It's a complete

blunder of the job, about as bad an arrangement for surround

sound with four channels as one could devise. If there is

but one lesson to be learned via this introduction, it's the

graphic one visualized above. Sometimes

the eye can fool the ear into thinking things are fine and

jolly, when they ain't. We can all count the four corners of

a typical room (har-dee-har, my studio is semi- trapezoidal,

and has SIX corners!) or studio. When the first quadraphonic

sound was being introduced in the early 70's guess where

they put the speakers (you've had enough hints)? Yup, just

like the image above, one for one. It also seemed like a

nice, democratically evenhanded approach, we have 360

degrees to split up, let's see now, 4 goes into 360... And

we get this "classic" setup in name only. It's a complete

blunder of the job, about as bad an arrangement for surround

sound with four channels as one could devise. If there is

but one lesson to be learned via this introduction, it's the

graphic one visualized above.

Take a look with your

foolish eyes once again. 90 degrees is a pretty wide angle

to try to fill with two speakers. Even from the equidistant

"sweet spot" as the seat above is located, you will find

images tend to vanish when they are midway between the

speakers. You have another classic going on here,

stereophonically speaking, a "hole in the middle." Add the

two other channels and what you get is FOUR holes in the

middle. You end up with sound that can only be precisely

heard from but four spots. Everywhere else is an omniphonic

spread of hard-to-point-to vagueness. It gets worse. Try

listening to a normal stereo system (about 45 to 60 degree

speaker separation) with your back to the speakers. Hmm...

the stereo sort of collapses inwards, doesn't it? I'm not

trying to lay any dogma on you. These are simple matters to

try out with your own ears, as is all the stuff on this

page. We all were surprised to learn how things are not so

obvious as we first think they'll be.

And it gets worse

again. When you face forward, you can hear any speaker

located in front of you, and follow it as it moves to the

exact side, either side, whereupon it will sound like it's

moving back in towards the middle again, but without the

same precision when the speaker moves behind your head.

Again it works on both sides the same way. All stereo relies

on the fact that our ears will hear "ghosted" virtual images

of sounds located between any no too widely separated

loudspeakers, if the distances, phases, and sound levels are

correctly adjusted. But aside from some very clever tricks

heard from exacting positions and setups, you normally won't

hear sounds come from outside of a pair of speakers.

The result is that you

can image sounds rather well in central locations, with

speakers moved to each side a bit, but those speakers set

the maximum width you'll be able to reproduce well. Think

about those two speakers behind you in the view above. Their

sounds are towards the center, just like the front pair. So

there's nothing that sounds like it's coming from the sides.

The only way to fill in the side "hole" is by locating a

speaker there, one on each side works splendidly. After you

have normal stereo there is no better place to locate the

next two channels than exactly to either side of you. That

also works when you add a 5th channel, as the latest

surround sound systems do. Like this:

The

Worst Surround Setup -- 5 Channels

This

view is of the worst possible use of five channels. Now one

of the black holes in the middle is filled in, leaving just

three of them. The sounds up front are fine, wide and very

decently positioned. There are no sound to the sides of

those speakers, though. Everything comes mainly from within

this right angle of two 45 degree sectors. What about the

rear channels? Well, they will be heard, of course, but the

stereo will be poor compared with that in front. Not only is

there no central rear speaker, but the back positions are,

like before when you tried this yourself, not definitely

locatable. Any poor stereo effect is narrowed when it's

completely behind us. Those two channels are being wasted,

just as they were with most quad sound in the 70's. Little

wonder an honest public might be less than impressed, when

confronted with the truth of their own two ears.

The first four channel

setup I had, when my studio was in the brownstone, as shown

in many phonos on our website, was exactly as the first of

these two views shows you. That was folly on my part,

because I should have known better, having made many four

channel recordings years before with that custom Viking tape

deck. I tried placing microphones in that same shape, then

the speakers when I played the tapes back. I tried all of

them way up in front in various shapes. I tried a "diamond",

with one channel up in front, one directly in back, and one

on each side. That was much better, but the holes in the

middle were irritating, and I was never sure if a certain

sound was exactly in front of me, or exactly behind me. Once

more I beg you to try this all out for yourself. You can

certainly record two channels at a time, and see what

happens when the two speakers are center front and center

back, then again one on each side, and so forth for each

possible pairing. Play the recording in the dark or with

your eyes closed. Invite friends and other sophisticated

audio buffs to listen with you and compare notes.

Again, you don't have

to take my word on this issue. David Greissinger, the

brilliant head designer for Lexicon for more than 25 years

wrote several scientifically researched papers for the AES

(Audio Engineering Society), the AAS (American Acoustical

Society), and others in the 80's and more currently. He

stumbled upon the very same discoveries which Rachel and I

had back in the early 70's (check

out our new bibliography

at the end of these pages).

Our lesson was painfully learned and was independently

reproducible, to boot. We had to rehire the same strong

electrician / handyman to return and relocate the rear two

speakers, positioning them up at the

sides

(a

compromise, speakers that high up can leak over the head

slightly to the opposite ear),

as you can see in the wider photos

of the brownstone studio.

The mistake was too painful to live with, and we had to

admit it and go with what our ears were telling us. When I

moved into here I didn't make the same mistake. Did it even

better, as I have a lot wider space. You can see how the

channels are located way above. In an arc, 180 degrees wide,

like those old Cinerama Screens. Then you more or less split

the angle into three parts, so the channels are located at

roughly 60 degree intervals. Or use the more

symmetrical arrangement

above. What's that old line?: "Try it, you'll like

it!"

|

(Top

of the Page)

(Top

of the Page)

Digression

II -- Listening Test to Try yourself Digression

II -- Listening Test to Try yourself

Standard

Stereo, both speakers in front of you

There's

something most valuable I learned during a valiant failure

to become a Physicist. Well, more than one, like keeping a

wary, skeptical eye out for deception, or the even more

common, self deception. But a lesson that holds in any field

at all is a willingness to be proven wrong. You are much

more likely to discover crumbs of truth if you don't

prejudge what you expect to find too closely, relying

instead on reality-checks and experimental tests. Unlike a

few sites I've seen that preach to the bleachers, I want you

to check out what I'm trying to describe here, not merely

take my word on it. Beware the newest Great Prophets who

claim possession of "the one true path." All of these ideas

here contain a margin for error, a tolerance, and have been

verified experimentally, not idle philosophy. You can alter

things to a degree away from what's here, before things will

weaken or fall apart. And you may discover even more refined

ways to handle each situation. There's

something most valuable I learned during a valiant failure

to become a Physicist. Well, more than one, like keeping a

wary, skeptical eye out for deception, or the even more

common, self deception. But a lesson that holds in any field

at all is a willingness to be proven wrong. You are much

more likely to discover crumbs of truth if you don't

prejudge what you expect to find too closely, relying

instead on reality-checks and experimental tests. Unlike a

few sites I've seen that preach to the bleachers, I want you

to check out what I'm trying to describe here, not merely

take my word on it. Beware the newest Great Prophets who

claim possession of "the one true path." All of these ideas

here contain a margin for error, a tolerance, and have been

verified experimentally, not idle philosophy. You can alter

things to a degree away from what's here, before things will

weaken or fall apart. And you may discover even more refined

ways to handle each situation.

A very modest test is

shown in this digression. You ought be able to try it

without any special equipment or setup, at home or in the

studio. One of the key reasons that many of the original

suggestions about Quadraphonic Sound in the '70's failed to

live up to their hype could have easily been found by a

curious person who was unwilling to go along with the party

line. Consider the four speakers, one per corner, concept

given in the previous digression. How does sound from the

front two channels get perceived, and is this much different

from the rear two channels of "obvious quad"? Try one

pairing at a time. Pick a few good CD's that exhibit

excellent sound, separation, and imaging/ambience. First sit

as shown just above, the usual way, centered in the "sweet

spot". Okay, note what you hear, essentially all the sound

in front. Now swing your chair around, so you're facing away

from the speakers, like this:

Face

the other way -- both speakers behind you

(well,

the chair is rotated around)

This

view is a pretty accurate metaphor for what you'll hear when

you rotate your chair around by 180 degrees. All the sound

now is located behind you. Keep the same music playing as

above, listen, then switch the way you face back and forth

several times to compare the differences you hear. The

speakers won't really edge closer together when you face

away, nor ought the directional information become oddly

blurred, but that's certainly the way it sounds! I was

rather shocked by this test when someone suggested it to me.

We had experienced the same problems with the crummy initial

layout we'd made in the brownstone studio, and knew

something fundamental was going on. But this elegant A/B

comparison is such a simple way to demonstrate the

principle. The way our ears are constructed we "funnel-in"

sounds easily from in front and sides with our built-in "ear

trumpets." Whatever comes from behind is masked by those

same bio-trumpets, robbing crucial mid and high frequencies

especially, the stuff of directionality.

Ever watch a cat rotate

its outer ears while listening intently? Theirs are even

larger proportionally than ours, and the horn effect must be

highly noticeable. They also have better muscle control over

them than we do, so they can redirect the aiming points to a

large extent. It can't be done simultaneously, but watch

them listen to a repeated, continuing sound, and how quickly

they are able to zero in on the exact direction. They can

adjust to, and adapt better than us in front/read

comparisons, so would undoubtedly come up with a

significantly different plan for Feline Surround

Sound...

But we're interested in

an optimum plan or two for Human Surround Sound. Since the

back of our heads is not nearly as sensitive to sound

directionality and nuance (not to mention a poorer frequency

response, and unfortunate interference as sounds move away

from the rear of one ear towards the rear of the other), we

ought not "waste" too much effort trying to obtain what we

can't: a uniform sound field. That's where so many surround

concepts fall down, assuming we humans can hear in 360

degrees and follow it all accurately.

|

©

Copyright 2001 Wendy Carlos -- All Rights

Reserved.

(Top

of the Page)

(Top

of the Page)

Back to the Wendy Carlos Home Page

Back to the Wendy Carlos Home Page

![]() Adventures

in Surround Sound, from 7.2 to Quad

Adventures

in Surround Sound, from 7.2 to Quad ![]() Introduction

Introduction![]() Nomenclature

and Full 7.2 channel setup

Nomenclature

and Full 7.2 channel setup![]() The

Main 5.2 Channels

The

Main 5.2 Channels![]() Digression

I -- Classic Blunders

Digression

I -- Classic Blunders![]() Digression

II -- Listening Tests

Digression

II -- Listening Tests![]() Digression

III -- Surround Options

Digression

III -- Surround Options![]() 5.1

Surround Sound for Music

5.1

Surround Sound for Music![]() 5.1

Surround Sound for Films

5.1

Surround Sound for Films![]() Optimum

Quadraphony

Optimum

Quadraphony![]() Quadraphonic

Folly

Quadraphonic

Folly![]() "Jousting

at Windmills"

"Jousting

at Windmills"![]() An

Infamous Letter to the Editor

An

Infamous Letter to the Editor![]() The

follow-up Letter to the Editor

The

follow-up Letter to the Editor![]() Something

about Matrix "Quad"

Something

about Matrix "Quad"![]() Psi-Networks

(the secret ingredient)

Psi-Networks

(the secret ingredient)![]() Recording

in Surround

Recording

in Surround![]() Quadraphonic

Recording

Quadraphonic

Recording![]() Multichannel

Recording Quirks

Multichannel

Recording Quirks![]() Shoulders

To Stand On (Bert

Whyte)

Shoulders

To Stand On (Bert

Whyte)![]() Bibliography

-- References

Bibliography

-- References![]() Go to the wendycarlos.com Homepage

Go to the wendycarlos.com Homepage

![]() Introduction

Introduction

![]() Finally

it seems to be happening! In 2001 we don't yet have Hal

(check back

in another 100 years ;^),

but we do have a distinct buzz-on about Surround Sound --

for film soundtracks, DVD's, and for music creation and

mixing, as the new DVD-A standard is designed to implement.

To me it seems like it's taken forever. I'd nearly given up

hope that a practical surround sound system would reach the

public in my lifetime, anyway. Those of us who lived through

the big Quad Boom and Bust of the 70's are gun shy,

expecting another stillborn standard, based more on hype

than reality, and something valuable gained for effort

expended. Just a few weeks ago I checked in again on what's

become available online in web pages around the globe. Well,

welly, there's a good representative amount of information

starting to appear already -- on Quad, 5.1

(five

full-range channels and one sub woofer with one tenth the

range, or ".1", total = 5.1),

and several other options. Yeay, this is a healthy sign!

Could it be?!

Finally

it seems to be happening! In 2001 we don't yet have Hal

(check back

in another 100 years ;^),

but we do have a distinct buzz-on about Surround Sound --

for film soundtracks, DVD's, and for music creation and

mixing, as the new DVD-A standard is designed to implement.

To me it seems like it's taken forever. I'd nearly given up

hope that a practical surround sound system would reach the

public in my lifetime, anyway. Those of us who lived through

the big Quad Boom and Bust of the 70's are gun shy,

expecting another stillborn standard, based more on hype

than reality, and something valuable gained for effort

expended. Just a few weeks ago I checked in again on what's

become available online in web pages around the globe. Well,

welly, there's a good representative amount of information

starting to appear already -- on Quad, 5.1

(five

full-range channels and one sub woofer with one tenth the

range, or ".1", total = 5.1),

and several other options. Yeay, this is a healthy sign!

Could it be?!

![]() (Top

of the Page)

(Top

of the Page)![]() Nomenclature

and Full 7.2 Monitoring

Nomenclature

and Full 7.2 Monitoring![]() Since

the 60's I've been using four or more channels on the

mixdowns of most of my performances and compositions. It's

been a life's desire to get some of this surround music into

the hands of music listeners. And that may very well be

happening soon. I also discover I've accumulated quite a few

"barnacles on the hull" from working in multichannel sound

all these decades. I'd like to scrape some of these off onto

the next generation to figure out what the $%#* to do with

some of them! That was the major motivation for creating

this web location. We'll be referring to speaker

arrangements (very important, that) and the several output

channels a lot on these pages. So let's show the

near-standard labels we'll be using. Here's the same image

at the top, smaller and with labels in red pasted over the

front of each speaker. The two subwoofers are down below

this view, on the studio floor one step below the level of

this shot, and so we've just positioned arrows that show

where they physically are located. There's nothing

surprising going on here, but we wanted to define our terms

clearly.

Since

the 60's I've been using four or more channels on the

mixdowns of most of my performances and compositions. It's

been a life's desire to get some of this surround music into

the hands of music listeners. And that may very well be

happening soon. I also discover I've accumulated quite a few

"barnacles on the hull" from working in multichannel sound

all these decades. I'd like to scrape some of these off onto

the next generation to figure out what the $%#* to do with

some of them! That was the major motivation for creating

this web location. We'll be referring to speaker

arrangements (very important, that) and the several output

channels a lot on these pages. So let's show the

near-standard labels we'll be using. Here's the same image

at the top, smaller and with labels in red pasted over the

front of each speaker. The two subwoofers are down below

this view, on the studio floor one step below the level of

this shot, and so we've just positioned arrows that show

where they physically are located. There's nothing

surprising going on here, but we wanted to define our terms

clearly.

srndsm.jpg)

![]() (Top

of the Page)

(Top

of the Page)![]() (Top

of the Page)

(Top

of the Page)![]() Digression

I -- Classic Blunders to Avoid

Digression

I -- Classic Blunders to Avoidsrndsm.jpg)

![]() Sometimes

the eye can fool the ear into thinking things are fine and

jolly, when they ain't. We can all count the four corners of

a typical room (har-dee-har, my studio is semi- trapezoidal,

and has SIX corners!) or studio. When the first quadraphonic

sound was being introduced in the early 70's guess where

they put the speakers (you've had enough hints)? Yup, just

like the image above, one for one. It also seemed like a

nice, democratically evenhanded approach, we have 360

degrees to split up, let's see now, 4 goes into 360... And

we get this "classic" setup in name only. It's a complete

blunder of the job, about as bad an arrangement for surround

sound with four channels as one could devise. If there is

but one lesson to be learned via this introduction, it's the

graphic one visualized above.

Sometimes

the eye can fool the ear into thinking things are fine and

jolly, when they ain't. We can all count the four corners of

a typical room (har-dee-har, my studio is semi- trapezoidal,

and has SIX corners!) or studio. When the first quadraphonic

sound was being introduced in the early 70's guess where

they put the speakers (you've had enough hints)? Yup, just

like the image above, one for one. It also seemed like a

nice, democratically evenhanded approach, we have 360

degrees to split up, let's see now, 4 goes into 360... And

we get this "classic" setup in name only. It's a complete

blunder of the job, about as bad an arrangement for surround

sound with four channels as one could devise. If there is

but one lesson to be learned via this introduction, it's the

graphic one visualized above.srndsm.jpg)

![]() (Top

of the Page)

(Top

of the Page)![]() Digression

II -- Listening Test to Try yourself

Digression

II -- Listening Test to Try yourselfsrndsm.jpg)

![]() There's

something most valuable I learned during a valiant failure

to become a Physicist. Well, more than one, like keeping a

wary, skeptical eye out for deception, or the even more

common, self deception. But a lesson that holds in any field

at all is a willingness to be proven wrong. You are much

more likely to discover crumbs of truth if you don't

prejudge what you expect to find too closely, relying

instead on reality-checks and experimental tests. Unlike a

few sites I've seen that preach to the bleachers, I want you

to check out what I'm trying to describe here, not merely

take my word on it. Beware the newest Great Prophets who

claim possession of "the one true path." All of these ideas

here contain a margin for error, a tolerance, and have been

verified experimentally, not idle philosophy. You can alter

things to a degree away from what's here, before things will

weaken or fall apart. And you may discover even more refined

ways to handle each situation.

There's

something most valuable I learned during a valiant failure

to become a Physicist. Well, more than one, like keeping a

wary, skeptical eye out for deception, or the even more

common, self deception. But a lesson that holds in any field

at all is a willingness to be proven wrong. You are much

more likely to discover crumbs of truth if you don't

prejudge what you expect to find too closely, relying

instead on reality-checks and experimental tests. Unlike a

few sites I've seen that preach to the bleachers, I want you

to check out what I'm trying to describe here, not merely

take my word on it. Beware the newest Great Prophets who

claim possession of "the one true path." All of these ideas

here contain a margin for error, a tolerance, and have been

verified experimentally, not idle philosophy. You can alter

things to a degree away from what's here, before things will

weaken or fall apart. And you may discover even more refined

ways to handle each situation.srndsm.jpg)

![]() Go

on to Pt. II

Go

on to Pt. II![]() (Top

of the Page)

(Top

of the Page)

![]() Back to the Wendy Carlos Home Page

Back to the Wendy Carlos Home Page![]()